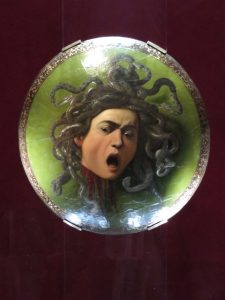

Caravaggio: Medusa, 1598 Oil on canvas on convex shield. Uffizi Gallery Florence

“Corallina” (particular) by Beatrice Brandini

On Monday 17 February, eight new rooms were inaugurated in the prestigious Uffizi Museum, wing of the Levante, dedicated to Caravaggio and 17th-century painting.

Eight rooms characterized by evocative names such as: “Caravaggio: the Medusa”, “Caravaggio: the Bacchus”, “Galileo and the Medici”, “Caravaggio and Artemisia”, just to name a few, but definitely suggestive is the beauty of the exhibited works.

Caravaggio: Bacco, Olio su tela. Firenze Galleria degli Uffizi

Artemisa Gentileschi: Giuditta che decapita Oloferne

The main actor is Caravaggio, the absolute protagonist of seventeenth-century painting, a strong personality, brilliant, passionate, he who used the light in a revolutionary manner, he who used “popular” subjects to reach the truth, the one to whom they were rejected masterpieces because they were considered scandalous and irreverent; a tormented life, always poised between legality and illegality, between fame and poverty, between protection and danger.

Gerrit van Honthorst, detto Gherardo delle Notti: Adorazione del Bambino

Bartolomeo Manfredi: Carità romana

I am no longer so passionate about ancient painting, but I appreciate the twentieth century with all its modern turmoil, however, I recognize, like everyone, the masterpieces of Giotto, Piero della Francesca, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Pontormo …, artists of extraordinary technique and from the revolutionary vision. But always, among all, I preferred Caravaggio.

When I was a student of art history, was Caravaggio a fulguration, his dramatic realism, his testament to the humble (should not it be the basis of religion, charity towards the outcasts?), his rejection of the beautiful mannered, so in vogue in the commissions of the time, his constant and personal thought of death, the rejection of conventions … all seemed to me anarchic and contemporary aspects, making me fall in love with this innovative artist.

Glimpses of the new rooms dedicated to 17th century painting

Rembrandt: Ritratto di giovane

Gerrit van Honthorst, detto Gherardo delle Notti: Cena con suonatore di liuto

Peter Paul Rubens: Giulietta e Oloferne

Caravaggio: Incredulità di san Tommaso

The uniqueness of Caravaggio, however, is his pictorial technique, a naturalism translated into the subjects and the atmospheres, the lack of illumination (the light) that makes his scenes dramatically theatrical; the volumes of the bodies, the faces, suddenly come out of the darkness, focusing only on them, on the subjects from which the spectator can not avoid looking.

The mayor of Florence Dario Nardella and the director of the Uffizi Eike Schmidt cutting the ribbon at the opening of the rooms dedicated to 17th-century painting and to Caravaggio

Caravaggio never pursued a canon of perfection, the beauty of classical art or the great Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo or Raffaello, he was interested in the truth (in his still lifes, scholars have been able to understand what illness the plants represented by the artist); here is the dry leaf, the withered fruit, the saints who do not seem saints. Caravaggio used subjects, objects or scenes familiar to him because only then could he tell his truth.

Caravaggio: Medusa, 1598 Oil on canvas on convex shield. The monstrous look of the Medusa mutated the men in stone, therefore to represent her in the shield to face the enemy, was to hope for the best performances. But beyond the originality of the medium used, the extraordinary nature of this painting is the realism of the expression of the Medusa, as well as the revolutionary use of light / shadow, Caravaggio in fact transforms the convexity of the shield into apparent concavity.

After his death, Caravaggio was forgotten for centuries, it is only thanks to some enlightened men (like Roberto Longhi), who have been able to resume the threads of this extraordinary life, that the work of Caravaggio was rediscovered and considered revolutionary, a painting like affirmation of the truth, a marvelous painting.

“Corallina” by Beatrice Brandini

Good life everyone!

Beatrice